|

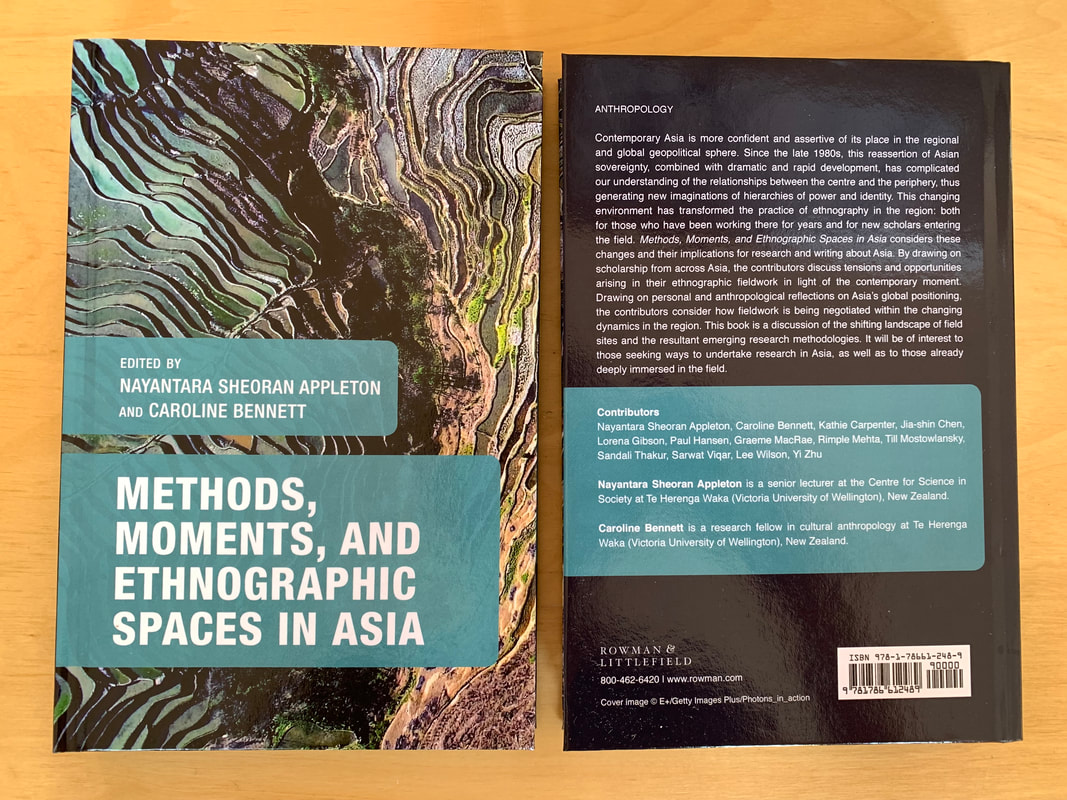

Drs. Caroline Bennett and Nayantara S. Appleton In 2021 we published an edited volume, Methods, Moments, and Ethnographic Spaces in Asia. Taking Kuan-Hsing Chen’s Asia as Method: Toward Deimperialization (2010) as a prompt, and drawing on ethnographic research from across the Asian continent, we aimed to address a dearth in the literature that positioned Asia as a centre – not only in relation to geopolitical and economic shifts, but also to methodological approaches.

The book launched while the COVID-19 crisis was still hitting hard and shaping our personal realities alongside the larger medico-political global shifts. Since the publication of the book in 2021, we have both moved across the world (although Nayantara returns to Aotearoa later this year). But in June this year, we met in Sri Lanka and re-visited the book together - wondering whether the points we had initially set out to address, starting in 2017 and culminating in 2020 when we send the book to publication, were still relevant. These conversations have prompted us to blog about the book for our larger NZASIA community and whanau, many of whom were involved in its writing. On re-visiting/re-reading the book, now two years on from its publication, the themes of the book seem acutely pertinent. Indeed, the COVID-19 pandemic illuminated and highlighted many of the geopolitical and social considerations highlighted by our authors – including the role of migration and movement (or its curtailing), the obscuring or highlighting of political landscapes, and the positioning of ourselves as researchers vis-à-vis the field. These conversations about research and research methods in changing Asian landscapes – in relation to other spaces in Asia itself – are as vital today as they were in 2021. The volume began as a conversation between two colleagues and friends about our respective work in Asia – Nayantara in India, and Caroline in Cambodia. As different authors came onboard it expanded to include thinking about subjects as wide ranging as mobility and verticality in the Western Pamirs (from Till Mostowlansky); infrastructure in Pakistan (Sarwat Viqar); psychiatric practice and positionality as a researcher-practitioner (are we translators, cartographers, or compradors?) (Jia-shin Chen); the complex relations of corporate retail of a Chinese researcher in a Japanese company in Hong Kong (Yi Zhu); how comparison provides linkages across Asia, Melanesia, and Oceania (Lorena Gibson); the evolution of Bali as place and product (Graeme Macrae and Lee Wilson); how multispecies ethnography of Japan from a Japanese family allows us to highlight that ‘we have always been cosmopolitan’ (Paul Hansen); and repositioning the self and the research vis-à-vis the relationality of women (including those from Bangladesh) in the borderlands of India and Nepal (Rimple Mehta and Sandali Thakur). Our own chapters consider the Asian experiences of feminist ethnography and participant movement (Nayantara) and the ongoing effects of the Cold War in Cambodia (Caroline). Thus, our authors, and the chapters in the volume as a whole, present a view on new renderings and imaginations of Asia from both within and outside the region – which in this new COVID-19 reality seem ever so pertinent. Each chapter offers personal reflection, and comes from long and ongoing wrestling with changing spaces and realities within our fieldsites as well as our disciplines. The linkages between these subjects were strong, despite them coming from across the huge geographical space and widely disparate social, economic, and political realities of Asia. And so, as part of the political project of this work, as well as a methodological interrogation, we also took a pan-Asian approach. At first, we received pushback from the publishing houses about this approach. Books sell better, they contended, if they have a regional focus, and Asia has longstanding subdivisions within which we might like to focus. However, this was a political project for us, as well as an invitation for new ways of thinking and positioning ourselves and the field. These subdivisions themselves were built in colonialism and hide the multiple ways Asia is and has been constructed across the centuries, including through religions (such as Buddhism or Islam), via trade along the (multiple) Silk Roads, or in geopolitical strategic focus. This pan-Asian approach is also fitting with Chen’s approach. Chen insists that ‘Asia as method’ is not a project of nation-states or subregions. There have always been multiple Asias, and Asia has had linkages and divisions across itself for centuries. But to see Asia in relation to Asia allows for the region to understand itself better in terms of its neighbours, as opposed to being in a peripheral relationship to Euro-American spaces and political projects. With all of this combined, the chapters in the book highlight the importance of Asia and the scholarship that emerges for/of/from this space, be it methodological, practical, or theoretical. For our readers, students and scholars alike, the book offers opportunities for seeing similarities across Asian spaces, points of differences, and areas of collaboration. But above all the chapters are beautiful ethnographic and personal narratives that invite us all to see Asia anew.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

The views expressed in these blogs are not those of the NZASIA Executive and reflect the personal views of the blog authors.

Archives

December 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed