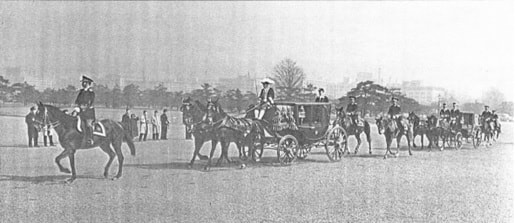

[Special Contribution] NZ-Japan Relations in the 1950s – Reminiscences for a 70th Anniversary10/1/2023 The timing of New Zealand’s post-war representation in Japan was not determined solely by what the Cabinet in Wellington thought it could or should afford – as was the case elsewhere. New Zealand had no posts anywhere in Asia until the 1950s. Pre-war foreign representation to a New Zealand not yet sure of its independence had merely been at Consular level, including in Japan from 1938, while formal relations were through London. But as Wellington debated which capitals were most urgent to be filled, a peace treaty with Japan had first to be negotiated in a climate of widespread post-war hostility. At the end of the war New Zealand had a seat on the Far Eastern Advisory Committee in Washington (the ‘Advisory’ later dropped on Soviet insistence), occupied officially by Heads of Mission Walter Nash and then Carl Berendson, but in practice usually by their deputies in Washington, John Reid (my father) or Dick Powles. It had no power really to control General MacArthur’s Occupation policy, but could irritate him with questions and demands. Australia and New Zealand generally represented a more hawkish and punitive position than MacArthur’s in line with their countries’ wartime bitterness, but New Zealand seemed often useful to the Americans as a more moderate counter to Australia.[1] A peace treaty was eventually signed in 1951, and formal diplomatic relations agreed the following year. Japan opened a Legation in Wellington, but New Zealand sent only a Trade Commissioner, Gordon Challis, “a rather rough diamond” who could cause offence, in the view of the Australian Ambassador, Sir Alan Watt. Cold War commitments finally encouraged New Zealand to spend a little more on Asian missions in the mid-fifties. Foss Shanahan was appointed to head New Zealand’s first full diplomatic mission in Asia in August 1954, even if for largely military reasons, and based in not-yet-independent Singapore. Tokyo followed soon after, and John Reid arrived in July 1955, first as Minister, later Ambassador, from New Zealand to Japan. Post-war Japan was hungry for recognition and legitimacy after the trauma of the 1940s, and still put on a spectacular show for the arrival of each new foreign envoy. John Reid was one the last of them to present his credentials to the Emperor with the full spectacle of a traffic-stopping state procession to the palace, designed to more than match the glitter of the European monarchies. Within a week of his arrival three London-built carriages arrived at the New Zealand residence to collect the envoy and his party, dressed in morning suites and top hats. Each carriage was drawn by two black horses, with coachman and footman in cocked hats. They were accompanied by 14 horsemen of the Imperial Guard. Traffic was halted for the precise 23 minutes of the carefully choreographed procession. At the palace the envoy was given exact instructions about the ritual, as presumably were the palace officials and Foreign Minister, including 4-5 minutes of strained conversation. My father must have been anxious about this unaccustomed pageantry, though his liking for amateur theatricals may have stood him in good stead. But he noted “I was so affected by the obvious nervousness of the Emperor that I missed out a sentence of my carefully memorized statement.” This spectacle was discontinued soon after. Many New Zealanders wanted nothing to do with Japan after the war, so that the diplomats’ job was to restore a respectful normality, to do his utmost to boost trade, and to encourage both sides to exploit the opportunities for productive trade. A bilateral trade agreement came into force in November 1957, a few months after the Australian equivalent. Nobusuke Kishi was the Japanese Prime Minister (Feb 1957 to July 1960) for most of John’s term. He was the most successful survivor of the wartime military-backed politicians, having escaped a war crimes trial by his shrewd adoption of a pro-American policy, hawkish towards communists. He saw the Southeast Asia and Australasia as the great opportunity for Japan’s post-war economic expansion. These were the countries he first visited after taking over as Prime Minister, including New Zealand in November 1957. When John Reid asked him his impressions the response was that it was beautiful - “like one big golf course”. Labour’s Walter Nash came to power in Wellington as Prime Minister (and Foreign Minister) at the November 1957 elections, at the age of 76. An indefatigable traveller, as well as friend and patron of John Reid since the 1930s, he made an official visit to Japan in February 1959. Rugby proved one of the early successes of the re-established relationship. Always associated with the Japanese aristocracy and its British connections, rugby had been discouraged under the military government. It made a strong revival after 1945, encouraged first by the Oxford-educated brother of the Emperor, Prince Chichibu, and later by his Anglophone widow, Princess Chichibu (1909–95), a valued dinner guest of my parents. But Japan had entertained no international team beyond the status of Oxford University until 1958, when the Junior All Blacks made their first international outing to Japan under Wilson Whineray’s captaincy. The New Zealand tour was a great boost to the game in Japan. I have not discovered where the initiative for this innovative venture lay. John Reid would certainly have been keen, having played at first five-eighths (fly-half) for his Petone High School and for Victoria University, and he became a beneficiary of the goodwill it produced. He was appointed Patron of the Japan Rugby Football Union for the remainder of his time in Tokyo, and donated a plaque which the JRFU used as a trophy for Annual All Japan Inter-Club Championships. Gaijin (expat) life in Tokyo was expanding rapidly in the 1950s, and even a small mission like New Zealand’s could play its part. My father took great pleasure in the anglophone Tokyo Amateur Dramatic Society (TADC) and became its active president, joining in the monthly play-readings and quarterly public performances, including an annual Shakespearian play for the Japanese students of English literature. He was also prominent in St Alban’s Church, then one of only three English-speaking parishes within the Japanese Province of the broader Anglican communion -- Nippon Sei Ko Kai (NSKK). Although with zero Japanese he must have had trouble following proceedings, John Reid somehow represented the laity of St Albans at a synod to choose a new bishop. Meanwhile my mother adapted to then-typical activity of expat wives, studying ikebana, making cultural outings with an international group called No Desko Kai, and chairing the fund-raiser International Charity Ball in 1958. My parents did their best to persuade their Japanese guests to develop a taste for New Zealand lamb, with notable lack of success. The major New Zealand item filling Japanese ships on their return from New Zealand, by volume if not value, turned out to be scrap metal. The ships did not take passengers, but nevertheless my brother and I were given a cabin to Japan on the Nikko Shosen line’s Tenwa Maru for the University vacation at the end of 1957. By hindsight this kind of largesse from a corporation cannot have been strictly proper, but my father appears to have accepted it as part of a Japanese gift-giving culture he should accommodate to. I had just finished my first year at Victoria, and my brother Paul his architecture degree in Auckland. For us the spartan shipboard existence and the luxurious diplomatic lifestyle in Tokyo were equally strange and fascinating. Only the first engineer of the Tenwa Maru had enough English to begin our education in things Japanese; with the cook we had always inscrutable exchanges that bore little relation to what we consumed, but it was a huge relief when we were allowed to share the delicious noodles of the officers. But the Captain was unforgettably inventive and persuasive in mixing his few words of English with brilliant acting. Japan was a wondrous revelation to both my brother and I. Paul had already absorbed some admiration for Japanese architecture and made the most of our trip to Kyoto and some contacts with foreign architects practising in Japan. I was an 18-year-old student of history and politics, naively seeking to understand all that was different and beautiful. Since I was active in the Student Christian Movement at Victoria, a meeting had been arranged for me with some analogous group at the Kansei Gakuin University in Nishonomiya. I remember naively commenting that the Japanese seemed a very religious people, since I had visited so many temples over the New Year holiday. The students put me straight, that this was one of the most firmly secular societies in the world. Japan was still a poor society in comparison with New Zealand, and I recall the Kiwi discomfort of dealing on the one hand with servants (at the embassy) and on the other with beggars. Travelling to Kyoto on a pre-Shinkansen train, I annoyed my brother and his friend by yielding my expensive seat to an elderly lady who didn’t have one, requiring the three of us to take turns standing all the way to Kyoto. On the more crowded urban commuter trains we would sometimes be squashed by the crowd through different doors of a carriage, but I had no problem seeing my brother’s head above the mass at the other end. The contrast was extraordinary with my second visit to Japan in 1973, when the post-war babies had grown to my height. I ended up specialising on Indonesia rather than Japan, as the Asian country I had visited earlier and for longer, and whose problems seemed more urgent. But this early visit began a kind of love affair with Japan, whose culture, food, politeness and intelligent difference never ceased to appeal and intrigue. It does no harm that my work seems more appreciated there than elsewhere (outside Aceh!). [1] New Zealand’s role merited a volume in the Documents on New Zealand External Relations series--The Surrender and Occupation of Japan, ed. Robin Kay (Wellington: Government Printer, 1982). My father’s role in Washington and later in Japan is more fully discussed at pp.72-4 and 172-86 in my New Zealand’s Early Steps in Asia: A Biography of John S. Reid and Family (Canberra: Privately published online, May 2020), 201 pages, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2744707226/view John Reid with Master of Ceremonies Kuroda in the lead carriage At Tokyo airport to greet Nash, from Left, Ishigawa (protocol), Nash, Reid, Kishi Crown Prince (later Emperor) Akihito, flanked by John Reid and the team manager, about to greet the players at opening match against Waseda The Tenwa Maru Captain joins us at deck quoits

0 Comments

|

The views expressed in these blogs are not those of the NZASIA Executive and reflect the personal views of the blog authors.

Archives

December 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed