[Special Contribution] NZ-Japan Relations in the 1950s – Reminiscences for a 70th Anniversary10/1/2023 The timing of New Zealand’s post-war representation in Japan was not determined solely by what the Cabinet in Wellington thought it could or should afford – as was the case elsewhere. New Zealand had no posts anywhere in Asia until the 1950s. Pre-war foreign representation to a New Zealand not yet sure of its independence had merely been at Consular level, including in Japan from 1938, while formal relations were through London. But as Wellington debated which capitals were most urgent to be filled, a peace treaty with Japan had first to be negotiated in a climate of widespread post-war hostility. At the end of the war New Zealand had a seat on the Far Eastern Advisory Committee in Washington (the ‘Advisory’ later dropped on Soviet insistence), occupied officially by Heads of Mission Walter Nash and then Carl Berendson, but in practice usually by their deputies in Washington, John Reid (my father) or Dick Powles. It had no power really to control General MacArthur’s Occupation policy, but could irritate him with questions and demands. Australia and New Zealand generally represented a more hawkish and punitive position than MacArthur’s in line with their countries’ wartime bitterness, but New Zealand seemed often useful to the Americans as a more moderate counter to Australia.[1] A peace treaty was eventually signed in 1951, and formal diplomatic relations agreed the following year. Japan opened a Legation in Wellington, but New Zealand sent only a Trade Commissioner, Gordon Challis, “a rather rough diamond” who could cause offence, in the view of the Australian Ambassador, Sir Alan Watt. Cold War commitments finally encouraged New Zealand to spend a little more on Asian missions in the mid-fifties. Foss Shanahan was appointed to head New Zealand’s first full diplomatic mission in Asia in August 1954, even if for largely military reasons, and based in not-yet-independent Singapore. Tokyo followed soon after, and John Reid arrived in July 1955, first as Minister, later Ambassador, from New Zealand to Japan. Post-war Japan was hungry for recognition and legitimacy after the trauma of the 1940s, and still put on a spectacular show for the arrival of each new foreign envoy. John Reid was one the last of them to present his credentials to the Emperor with the full spectacle of a traffic-stopping state procession to the palace, designed to more than match the glitter of the European monarchies. Within a week of his arrival three London-built carriages arrived at the New Zealand residence to collect the envoy and his party, dressed in morning suites and top hats. Each carriage was drawn by two black horses, with coachman and footman in cocked hats. They were accompanied by 14 horsemen of the Imperial Guard. Traffic was halted for the precise 23 minutes of the carefully choreographed procession. At the palace the envoy was given exact instructions about the ritual, as presumably were the palace officials and Foreign Minister, including 4-5 minutes of strained conversation. My father must have been anxious about this unaccustomed pageantry, though his liking for amateur theatricals may have stood him in good stead. But he noted “I was so affected by the obvious nervousness of the Emperor that I missed out a sentence of my carefully memorized statement.” This spectacle was discontinued soon after. Many New Zealanders wanted nothing to do with Japan after the war, so that the diplomats’ job was to restore a respectful normality, to do his utmost to boost trade, and to encourage both sides to exploit the opportunities for productive trade. A bilateral trade agreement came into force in November 1957, a few months after the Australian equivalent. Nobusuke Kishi was the Japanese Prime Minister (Feb 1957 to July 1960) for most of John’s term. He was the most successful survivor of the wartime military-backed politicians, having escaped a war crimes trial by his shrewd adoption of a pro-American policy, hawkish towards communists. He saw the Southeast Asia and Australasia as the great opportunity for Japan’s post-war economic expansion. These were the countries he first visited after taking over as Prime Minister, including New Zealand in November 1957. When John Reid asked him his impressions the response was that it was beautiful - “like one big golf course”. Labour’s Walter Nash came to power in Wellington as Prime Minister (and Foreign Minister) at the November 1957 elections, at the age of 76. An indefatigable traveller, as well as friend and patron of John Reid since the 1930s, he made an official visit to Japan in February 1959. Rugby proved one of the early successes of the re-established relationship. Always associated with the Japanese aristocracy and its British connections, rugby had been discouraged under the military government. It made a strong revival after 1945, encouraged first by the Oxford-educated brother of the Emperor, Prince Chichibu, and later by his Anglophone widow, Princess Chichibu (1909–95), a valued dinner guest of my parents. But Japan had entertained no international team beyond the status of Oxford University until 1958, when the Junior All Blacks made their first international outing to Japan under Wilson Whineray’s captaincy. The New Zealand tour was a great boost to the game in Japan. I have not discovered where the initiative for this innovative venture lay. John Reid would certainly have been keen, having played at first five-eighths (fly-half) for his Petone High School and for Victoria University, and he became a beneficiary of the goodwill it produced. He was appointed Patron of the Japan Rugby Football Union for the remainder of his time in Tokyo, and donated a plaque which the JRFU used as a trophy for Annual All Japan Inter-Club Championships. Gaijin (expat) life in Tokyo was expanding rapidly in the 1950s, and even a small mission like New Zealand’s could play its part. My father took great pleasure in the anglophone Tokyo Amateur Dramatic Society (TADC) and became its active president, joining in the monthly play-readings and quarterly public performances, including an annual Shakespearian play for the Japanese students of English literature. He was also prominent in St Alban’s Church, then one of only three English-speaking parishes within the Japanese Province of the broader Anglican communion -- Nippon Sei Ko Kai (NSKK). Although with zero Japanese he must have had trouble following proceedings, John Reid somehow represented the laity of St Albans at a synod to choose a new bishop. Meanwhile my mother adapted to then-typical activity of expat wives, studying ikebana, making cultural outings with an international group called No Desko Kai, and chairing the fund-raiser International Charity Ball in 1958. My parents did their best to persuade their Japanese guests to develop a taste for New Zealand lamb, with notable lack of success. The major New Zealand item filling Japanese ships on their return from New Zealand, by volume if not value, turned out to be scrap metal. The ships did not take passengers, but nevertheless my brother and I were given a cabin to Japan on the Nikko Shosen line’s Tenwa Maru for the University vacation at the end of 1957. By hindsight this kind of largesse from a corporation cannot have been strictly proper, but my father appears to have accepted it as part of a Japanese gift-giving culture he should accommodate to. I had just finished my first year at Victoria, and my brother Paul his architecture degree in Auckland. For us the spartan shipboard existence and the luxurious diplomatic lifestyle in Tokyo were equally strange and fascinating. Only the first engineer of the Tenwa Maru had enough English to begin our education in things Japanese; with the cook we had always inscrutable exchanges that bore little relation to what we consumed, but it was a huge relief when we were allowed to share the delicious noodles of the officers. But the Captain was unforgettably inventive and persuasive in mixing his few words of English with brilliant acting. Japan was a wondrous revelation to both my brother and I. Paul had already absorbed some admiration for Japanese architecture and made the most of our trip to Kyoto and some contacts with foreign architects practising in Japan. I was an 18-year-old student of history and politics, naively seeking to understand all that was different and beautiful. Since I was active in the Student Christian Movement at Victoria, a meeting had been arranged for me with some analogous group at the Kansei Gakuin University in Nishonomiya. I remember naively commenting that the Japanese seemed a very religious people, since I had visited so many temples over the New Year holiday. The students put me straight, that this was one of the most firmly secular societies in the world. Japan was still a poor society in comparison with New Zealand, and I recall the Kiwi discomfort of dealing on the one hand with servants (at the embassy) and on the other with beggars. Travelling to Kyoto on a pre-Shinkansen train, I annoyed my brother and his friend by yielding my expensive seat to an elderly lady who didn’t have one, requiring the three of us to take turns standing all the way to Kyoto. On the more crowded urban commuter trains we would sometimes be squashed by the crowd through different doors of a carriage, but I had no problem seeing my brother’s head above the mass at the other end. The contrast was extraordinary with my second visit to Japan in 1973, when the post-war babies had grown to my height. I ended up specialising on Indonesia rather than Japan, as the Asian country I had visited earlier and for longer, and whose problems seemed more urgent. But this early visit began a kind of love affair with Japan, whose culture, food, politeness and intelligent difference never ceased to appeal and intrigue. It does no harm that my work seems more appreciated there than elsewhere (outside Aceh!). [1] New Zealand’s role merited a volume in the Documents on New Zealand External Relations series--The Surrender and Occupation of Japan, ed. Robin Kay (Wellington: Government Printer, 1982). My father’s role in Washington and later in Japan is more fully discussed at pp.72-4 and 172-86 in my New Zealand’s Early Steps in Asia: A Biography of John S. Reid and Family (Canberra: Privately published online, May 2020), 201 pages, https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-2744707226/view John Reid with Master of Ceremonies Kuroda in the lead carriage At Tokyo airport to greet Nash, from Left, Ishigawa (protocol), Nash, Reid, Kishi Crown Prince (later Emperor) Akihito, flanked by John Reid and the team manager, about to greet the players at opening match against Waseda The Tenwa Maru Captain joins us at deck quoits

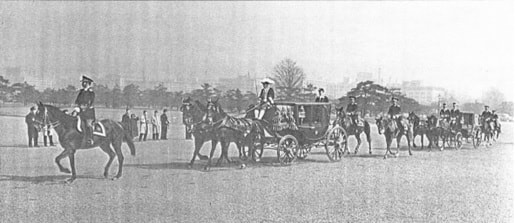

0 Comments

Dr Tadashi Iwami The former All Blacks’ superstar, Richie McCaw, is back in Japan after three years. Despite quite sticky weather in Tokyo, he seems to be enjoying his time there, as far as his Facebook photo is concerned. For New Zealand, Japan is not like its neighbour, Australia. There is an over 9,000km gap in distance, and it takes about 12 hours from Auckland to Tokyo. Yet, Mr McCaw and other more New Zealanders have visited Japan. In fact, prior to COVID19, the number of visitors from New Zealand nearly doubled from 49,400 in 2015 to 94,100 in 2019. In turn, about 100,000 Japanese people visited New Zealand. Per population, Kiwis love to visit Japan way more than Japanese do. Both countries are distant when it comes to geography, but they are close in many ways.

The bond that New Zealand and Japan have built is showing its strength in recent years. Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern chose to visit Japan as one of the first ‘must-go’ destinations. After making a quick visit to Singapore, Ardern landed Tokyo and met her counterpart, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, on 21 April 2022. Kishida was not new to New Zealand; he had come to New Zealand as a foreign minister in 2013 during the National government. Also, this year is the 70-year anniversary of the establishment of the diplomatic relationship between New Zealand and Japan. Looking back, their relationship has dramatically changed over time, from the brutal enemy in Malaya, the Solomon Islands and many more in the Pacific, being prisoners of wars in Featherston, A-class war criminals judged by Sir Erima Northcroft in the Tokyo Tribunal, the newly independent sovereign state in 1952, a major economic counterpart, to a key partner ‘in advancing and protecting peace and security in the Indo-Pacific’ region. Ardern’s visit to Tokyo in April 2022 was symbolic in that the bond between New Zealand and Japan cannot be cut off by the global pandemic of COVID19. Today, New Zealand and Japan are working together to substantively address issues that are affecting the wider Indo-Pacific region including Pacific Island countries and beyond. Their common concerns include Russian aggression against Ukraine and its humanitarian crises, the rise of Chinese influence in the South Pacific exemplified by the China-Solomon Islands security deal, and the most serious challenge to the countries in the South Pacific, climate change. While they are aware of the limitations in political, legal and resource terms, New Zealand and Japan are tightening their security bond for those concerns. Both countries will be signing an information sharing agreement in the near future. They are also keen on holding their first bilateral military exercise for enhancing maritime security. To enhance their defence diplomacy, both governments send their defence attaché personnel to own embassies. Their first Foreign and Defence Ministers’ (2+2) Meeting is expected to be held soon. In the context of the South Pacific region, Japan held the first Japan Pacific Islands Defence Dialogue (JPIDD) in September 2021 and New Zealand participated in it. The same month, New Zealand welcomed Japan as an observer at the South Pacific Defence Minister’s Meeting. Economically, New Zealand and Japan are taking a shared leadership in regional and international fora such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP11), and Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RECEP). The US-led Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) is another free trade forum where both nations could enhance their bond. In the Joint Statement that Ardern and Kishida released in April 2022, both also agreed to use the Japan-led Pacific Islands Leaders’ Meeting (PALM) as another important forum for issues in the South Pacific region, such as climate change. For them, climate change is an “existential threat” to many partners in the PALM. Thus, “both leaders renewed their determination to contribute to the peace and stability of the region in cooperation with Pacific and other partners, based on shared values and in support of Pacific priorities.” The indigenous cultural revitalisation is something Japan can learn a lot from Aotearoa. As regional and international environments change, there is no doubt that New Zealand and Japan need to evolve their relationships, just like any other relationships we have with our partners, whānau and friends. However, there is also no doubt that their relationship also goes forward, not backwards, and even much closer than what we see today in the long term. Just like Mr McCaw, we can strengthen our bond by visiting each other more often and experiencing what they offer here and there in the post-COVID19 era. About the author: Dr Tadashi Iwami (PhD in International Relations, University of Otago) is a lecturer of International Relations at Hokkaido University. Dr Iwami's expertise is on international relations, security issues, foreign policy, and Japan in the Indo-Pacific region. His recent publications appear in the Pacific Review, Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, and East Asia: An International Quarterly. The Institute of Pacific Relations in China, and the New Zealand economists who were brought to central roles through shameless cronyism.

[Fourth Biennial Conference, Institute of Pacific Relations, Shanghai China 1931] Date: Thursday, 18 August Time: 5 pm – 6 pm Venue: AM104, Alan MacDiarmid Building, VUW (map to the venue) Zoom Link https://vuw.zoom.us/j/92093104497 RSVP: [email protected] Abstract Hailed by an American newspaper in the 1920s as ‘a lily in the barnyard of politics’, the Institute of Pacific Relations was established in the worthy, but as it turned out ultimately fallacious, belief that greater familiarity among the countries of the region would prevent any future conflict. It had as its mandate to commission and carry out research on matters relating to the Asia/Pacific region, and to convene a major international conference every three years. The National Councils of its 14 member states drew upon representatives from business, academia and public life. J.B.Condliffe, then Professor of Economics at Canterbury University College, was recruited in 1926 as the Hawaii-based Institute’s first Research Secretary. Under his guidance, research programmes focused heavily on China, including two landmark projects, one to build a database on land use in China, and another to examine economic and social problems associated with China’s industrialisation. To support work on these, he recruited first Bill Holland, one of his students at Canterbury, and then Brian Low, another Canterbury graduate. The resulting IPR studies, Land Utilisation in China and Land and Labour in China, made, and continue to make, a fundamental contribution to the understanding of the forces underlying China’s economic development in the Republican era. About the Speaker Chris Elder helped open the New Zealand Embassy in Beijing, and served as Ambassador to China from 1993 to 1998. He has researched and published on various aspects of China and New Zealand/China relations. The present paper draws upon interviews carried out in the congenial and insightful company of the late Michael Green 36 years ago, now triumphantly revisited. Debating Patriotism in Meiji Japan - Professor Takashi Shogimen

About this eventAs Japan was redefining itself as a modern nation state in the wake of the Tokugawa shogunal regime’s fall, political and intellectual leaders recognised that promoting patriotism was a priority, yet there was no consensus around what patriotism meant. Indeed, some intellectuals assimilated a variety of European and American patriotism, while others rehabilitated the traditional Japanese idea. Controversies around patriotism encouraged cross-pollination of relevant ideas through linguistic and conceptual translation. Furthermore, debating patriotism among intellectuals was one thing; preaching it to the wider public was quite another. At the beginning of the 1890s, some intellectuals deplored that most of the Japanese people had no idea about patriotism. By the end of the decade, however, a French missionary remarked that no nation was so enthusiastically patriotic as Japanese. The talk will trace the historical process of making the distinctively Japanese patriotism (chūkun aikoku) in the 1870s and 80s and examine how the idea was embraced by the Japanese nation rapidly in the 1890s. For any enquiries please contact Dinah Towle [email protected] Bio: Takashi Shogimen is Professor of History at the University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand. He has published widely on medieval European and modern Japanese political thought including seven sole-authored books. His 2013 monograph in Japanese on The Birth of European Political Thought (Nagoya: University of Nagoya Press) was awarded the 2013 Suntory Prize, one of Japan’s most esteemed national prizes for humanities and social sciences. His other books include Ockham and Political Discourse in the Late Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), The Structure of Patriotism (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2019) and, most recently, What’s Wrong with Obedience? (Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō, 2021). The Philippine general election on May 9 resulted in the victory of Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr. as president. Marcos Jr. is the son of former authoritarian leader, Ferdinand Marcos, who was ousted from power in the 1986 EDSA protests. Sara Duterte-Carpio, the daughter of current President Rodrigo Duterte, was elected vice-president. This roundtable will address some of the issues and trends arising out of the elections that may further undermine democracy in the Philippines as Marcos and Duterte-Carpio serve their six-year term.

Panelists:

Tuesday, 31 May, 4:00-5:30 pm Logie 613, University of Canterbury, and via Zoom (If you wish to attend via zoom, email [email protected] for the link) Bios Patricio N. Abinales is a professor of Asian Studies at the University of Hawaii-Manoa. An expanded edition of his book Making Mindanao: Cotabato and Davao in the Formation of the Philippine Nation State was re-issued by Ateneo de Manila Press. He co-wrote State and Society in the Philippines (2017) with his late wife Donna J. Amoroso. Juhn Chris P. Espia is a PhD Candidate at the Department of Political Science and International Relations, University of Canterbury. He is also an Assistant Professor at the Division of Social Sciences, College of Arts and Sciences, University of the Philippines Visayas. His research interests include state-civil society relations, disaster risk management, local governance, policymaking, and elections. Paul Hutchcroft is a professor of Political and Social Change in the Australian National University’s Coral Bell School of Asia Pacific Affairs. He is a scholar of comparative and Southeast Asian politics who has written extensively on Philippine politics and political economy. This talk addresses the criticism toward Asian wet markets as reservoir for zoonoses, a discourse emergent alongside the outbreak narrative of Covid-19 surrounding the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan. It unpacks the stigmatization of wet market — a term first popularized in Singapore in the 1970s, when wet markets were differentiated from air-conditioned supermarkets — and the misfire of considering such food market form as biosecurity risk. While it is crucial to examine the neoliberal form of large animal farms coupled with mega-sized food infrastructure in contemporary China, which stretches beyond the “threshold of domestication” as some anthropologists and evolutionary biologists have warned, Dr. Hsieh argues that central to the friction on wet markets is the politics of multispecies life and death entangled with precarious labor created in the economic boom-and-bust cycles in Asia. She suggests that a better understanding of how Asia’s food infrastructure intersects with local and international food regimes will be essential to our vision for a post-pandemic world. Dr. I-Yi Hsieh is an anthropologist based in Taipei. Her research interests are urban anthropology, multispecies urbanism, and anthropology of art. Her current ethnographic research project examines the global friction on wet markets, following the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, with a special focus on the multispecies web of life and death entangled in the East Asian food infrastructure. She is also working on a book manuscript tentatively titled “Insect, Fish, Flower, Bird: Private Collecting and Domestic Nature in Reform Era Beijing.” You can find her publications in Asian Anthropology, positions: asia critique, International Quarterly of Asian Studies, and Asian Theatre Journal. https://otago.zoom.us/j/99338707134?pwd=Q3IrdkhEODg3eEM0MkNGaWNrUzJPZz09 Password: 525701; Meeting ID: 993 3870 7134 Tuesday, 3 May 12 2022 on Zoom and in Arts 5C13 12:00 PM (NZ)

Shin Takahashi (Victoria University of Wellington) Funding available for NZ-based scholars working on Southeast Asia to attend

ASAA 2022 This award is proudly supported by The Nicholas Tarling Charitable Trust Deadline for proposals: 10 February 2022 Announcement: 28 February 2022 Event: Asian Studies Association of Australia Conference Dates: 5th - 8th July 2022 Venue: Monash University, Melbourne, conference hubs at Monash international campuses, and virtually The ASAA Conference 'Social Justice in Pandemic Times' will bring together academics, activists, artists, students, practitioners and community members from across disciplines with shared interest in Asia, including Asian communities in Australia and globally. The theme of Social Justice is particularly apt as the region grapples with complex issues in a time of COVID-19. The conference is open to all who wish to share their scholarship and hear about Asia. It seeks to create conversation between people working across Asia. We welcome inter-country and interdisciplinary research and, befitting the theme, we aspire to ensure speakers represent all walks of life and engage a diverse range of topics. Three awards will be funded by The Nicholas Tarling Charitable Trust (it is estimated that each award will cover the registration fee, return flights NZ-Australia, insurance of tickets, airport transfers, and four night’s accommodation): 1. Nicholas Tarling ASAA conference presentation (student). The total value of this award is NZ$2700. 2. Nicholas Tarling ASAA conference presentation (scholar). The total value of this award is NZ$2950. 3. Nicholas Tarling ASAA Keynote conference address. This award will support a person to present a keynote address at the ASAA, named the Professor Nicholas Tarling Keynote Address. The total value of this award is NZ$3683. In each case the awarded sum will be paid directly to the successful applicant by The Nicholas Tarling Charitable Trust to a nominated New Zealand bank account. The awardee will then be responsible for making their own arrangements to attend the Conference. How to apply You must submit by the due date the following to this email address: [email protected]

Eligibility You must be based in New Zealand You must work on Southeast Asia You must be eligible to travel to Australia Important note: Awarding of these grants is contingent on travel being permitted. If travel is not permitted due to ongoing Covid-19 restrictions the grant may cover virtual registration fees. All travel costs are to be insured by a travel agent, must be fully refundable and if the travel is not permitted due to Covid-19 restrictions, must be returned to The Nicholas Tarling Charitable Trust. Shin Takahashi (Victoria University of Wellington) Call for Papers

This workshop focuses on international mobilities and migration as a way to understand the impacts of WWII across the Asia-Pacific region. Crises, including war, famine, natural disasters, political upheavals (such as revolution), epidemics and pandemics, create human mobilities and migration on a large scale. WWII was no exception. Charles Tilly describes World War II as “one of the greatest demographic whirlwinds to sweep the earth” (Tilly 2006). This demographic whirlwind also swept through the battlefields of the Asia Pacific region. While there is substantial research on war mobilities in the European context (deportees, expellees, refugees, etc.), much less is documented about similar experiences in Asia and the Pacific, despite ample cases of such mobilities (forced labourers, POWs, evacuees, etc.). This disparity likely results from two factors. First, war histories tend to be researched within a paradigm of national history at the expense of inter-regional war mobilities. Second, international migration studies (IMS) have paid scarce attention to war migration/mobilities in Asia. This workshop will challenge dominant paradigms in both war histories and IMS and enrich various social histories of war. Types of war mobility and migration that this workshop is concerned with include, but are not limited to, the following: ・Military personnel as (coerced) mobile/migrant military labour ・Civilian internees and labourers as forced migrants of war ・Evacuees and deportees as forced migrants of war ・POWs as forced migrants and forced labourers of war ・Embedded journalists and war artists ・Military medical staff ・Religious missionaries The key factor that must be addressed is the crossing of borders, whether internal or external, across land or water. The period of war mobilities and migration for this workshop is set from 1931 to 1953. In East Asia there were several battles prior to 1941, including the Manchurian incident. And just five years after the end of WWII the Korean war began, so again the Asia Pacific region was fighting a war, with the line between hot and cold never clear. This workshop thus situates WWII within a chain of small and larger conflicts. Although the focal period is from 1931 to 1953, the impacts of war mobilities and migration created ongoing effects and the causes may have had roots prior to 1931. Therefore, the period from 1931 to 1953 may be flexibly interpreted as regards the causes and impacts of war mobilities. By identifying various types of war mobilities and migration, the transnational connections or disconnections resulting from them, and the manifested outcomes of these mobilities, this workshop aims to present complex histories of World War II and to shift familiar ways of understanding this war, and the empires and (changing) borders that have often defined it. Some key questions include: ・How did war mobilities and migration create new transnational connections or flows of ideas, while disconnecting other ones? ・How did war mobilities and migration challenge a regional framework by connecting Asia and the Pacific? ・How did war mobilities and migration impact on colonial structures and create different social realities and connectivities? ・How did war mobilities and migration reproduce and enforce colonial power structures? ・How did war mobilities and migration impact on gender roles and relations in colonial societies? ・How do war mobilities and migration in Asia and the Pacific enable us to contextualise this region in a world history of the Second World War? SUBMISSION OF PROPOSALS While scholars from any stage of their career are welcome to apply to attend this workshop, early career researchers (ECRs) are particularly encouraged as one of the key aims is to support ECRs. Successful PhD and ECR applicants will have the opportunity to attend a presentation training and feedback session with the convenors prior to the workshop. (ERC eligibility: PhD awarded no earlier than 2016; career interruptions are also considered). Selected papers from the workshop will be submitted to a Q1 journal (yet to be confirmed) as part of a special issue on war mobilities in the Asia Pacific War/WWII. Those selected for inclusion will be expected to work with the workshop convenors/special issue editors to revise their draft paper and to adhere to set deadlines. We anticipate publication in 2023/24. ◆Paper proposals should include: 1) a title; 2) an abstract (up to 500 words maximum); 3) a brief personal biography of 150 words); and 4) contact details. Please use the template for your paper proposal and submit your proposal to [email protected]. ◆Key dates 1) Deadline for submission: 17 January 2022 2) Notification of outcomes of your submission: by 14 February 2022 3) Workshop presentation mentoring for ECRs: TBA June 2022 4) Online workshop: 18 & 19 July 2022. Keynote Speaker: TBA WORKSHOP CONVENORS ・Dr Christine de Matos (Faculty of Arts & Sciences and Business & Law. The University of Notre Dame Australia) ・Dr Rowena Ward (School of Humanities and Social Inquiry, University of Wollongong, Australia) ・Associate Professor Yasuko Hassall Kobayashi (College of Global Liberal Arts, Ritsumeikan University, Japan) To contact the convenors Please send an email to [email protected]. ************************** This workshop is funded by an Event Grant for the 2021 round from the Asian Studies Association of Australia (ASAA) & by the Institute of Humanities, Human and Social Science, Ritsumeikan University. |

The views expressed in these blogs are not those of the NZASIA Executive and reflect the personal views of the blog authors.

Archives

December 2023

Categories |

||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed